Dear reader,

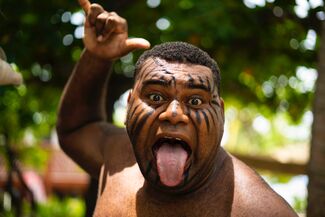

After escape games, cooking classes, and improv competitions, can you guess the fall-winter trend in team building exercises? The haka. What a time to be alive! For those who have never watched a rugby match featuring the All Blacks, the haka is a ceremonial dance originally practised by the Maoris and taken up since 1905 by the New Zealand national team. In its original form, tattooed men perform dance steps and facial contortions whilst chanting a poem or story specific to their tribe. In its corporate version, imagine a group of senior executives slapping their thighs energetically whilst sticking their tongues out... Crazy? Maybe not.

If it hadn’t been born in Polynesia centuries ago, the haka could have been invented by HR managers. Coordination, synchronisation, sung poetry, comradeship... What’s not to like? New Zealander Brad Edwards, founder of Kiwi Animations, a company offering corporate workshops, says it can be a great unifier. And to those about to cry cultural appropriation, don’t panic: each workshop includes a short history of the origins and meaning of this ritual dance. Only then does the real teamwork begin: participants make up their own song, choreography, facial expressions, put on their own makeup... and finally perform their homemade haka, in front of all their colleagues.

To the sceptics who might confuse the haka with any other ceremonial dance, remember that “haka” means both “to dance” and “to do”: it’s not entertainment but a mode of action. In Maori culture, the haka can take place before a conflict, but also to welcome neighbouring tribes or during collective celebrations... It’s a ritual to which the identity of a group is attached.

But in spite of all this, I’m afraid that the cohesion sold to us by the likes of Kiwi Animations might be fake. The problem isn’t so much the dance itself, but a grave misunderstanding of its purpose. The haka isn’t intended to boost commitment to a group: it’s part of a long mythological tradition, or at the very least, part of a very specific historical and social context. The members of the tribe recognise themselves in it because they have seen it done by their family and predecessors, and because they themselves have repeated it many times.

Quite the opposite, therefore, of corporate hakas! Because the whole point of these “inspiring” or “creative” workshops is that they’re presented as a break from everyday life – which is increasingly bogged down by isolation (due namely to remote work) and all kinds of pressure... The idea behind the corporate haka is to get to know your office neighbour and then get straight back to your everyday lives, enriched by just a few more private jokes and embarrassing moments you can’t forget. But without the depth it acquires through repetition, the haka is little more than a flashmob.

‘Through the haka, it is the mana of an entire society which is exposed to the eyes of all’

The real power of the haka lies in the mana it embodies. Mana: a quality received from above (from the gods, or ancestors) which allows victory (in war, in hunting, in fishing). But this polysemous word, which is found in most Polynesian languages, means a lot more than that. In their 1904 General Theory of Magic, Marcel Mauss and Henri Hubert try to define it as follows: “Mana is not simply a force and a being – it is also an action, a quality, and a state. In other words, the word is at the same time a noun, an adjective, and a verb.[…] It achieves this confusion of the agent, the rite, and things, which seemed to us to be fundamental in magic.”

Mana is at the same time a magical incantation, a qualifier which designates what is powerful and extraordinary, and a name which designates the force which holds things together and gives them consistency. It is therefore “both supernatural and natural, since it is widespread throughout the sensitive world, to which it is heterogeneous and yet immanent.” Rather than a mere signifier of the religious or the sacred, it is a form of expression of social life itself, in the multiplicity of its dimensions. In this way, Mauss and Hubert show that magic involves “collective representations” and structuring social beliefs – rather than obscure or purely individual rites. Through the haka, it is the mana of an entire society which is exposed to the eyes of all.

It’s perhaps no coincidence that some companies are now relying on the haka. In these times of permacrisis anxiety and questioning of the meaning of work, how can we not see it as a clumsy attempt to seek their salvation in magic? But that would be forgetting that it’s not the haka which creates mana, but the other way around. And this kind of magic, which underlies all attachment at work, is created through rituals that are certainly less spectacular, but just as important: the fit of nervous laughter before an important deadline, the lively lunches, the little quirks handed down to us by senior members of the company, moments of shared focus, in-house superstitions... In short: no mana? No haka.

Apolline Guillot